USING RADAR FOR SITUATIONAL AWARENESS

By Erik Eliel

Erik Eliel, the acknowledged expert on airborne weather radar use and training (www.rtiradar.com), has taught at the last three Twin Commander Universities. His radar training tips appear periodically in Twin Commander Aircraft�s Flight Levels update and monthly eLetter.

One of the pillars of professional piloting is the ability to maintain situational awareness (SA). As an instructor at the Air Force Advanced Instrument School, I had the opportunity to study a number of Controlled Flight Into Terrain (CFIT) accidents. There is one commonality you�ll find in every CFIT accident�a loss of SA, which can be either in the vertical or horizontal. In other words, the pilot got right, left, or below the black line whose sole purpose is to provide terrain separation. Notably, in many of these CFIT cases the loss of SA was preceded by task saturation. The high workload environment of single-pilot operations increases the risk of task saturation, and losing SA poses a serious threat. Clearly, being able to use available resources efficiently is paramount.

There was a time in my professional career when, like most pilots, I operated the radar mostly when weather appeared to present a threat. I�ve learned since that this is a flawed strategy, for a few reasons. Most significantly because it is predicated upon the false assumption that radar proficiency is instantaneous with the selection of the ON button.

Additionally, it implies that the �weather� radar is only for detecting weather. That may be its primary purpose, but in reality any object that reflects the transmitted energy back, which in turn is displayed in the cockpit, can assist in quickly building SA.

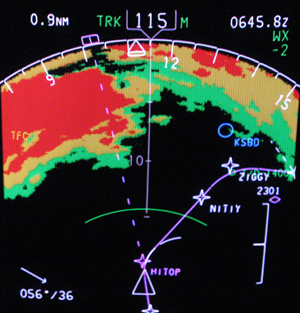

The image accompanying this article was taken on the ZIGGY FOUR arrival descending into Ontario, California, one very dark night with clear skies and no hazardous weather present. The displayed returns are mountains that bracket the arrival on both sides. Obviously, it was in my best interest to keep a high level of SA regarding this terrain.

The aircraft I fly has a reliable terrain awareness and warning system (TAWS), which uses a combination of aircraft positional data and an internal terrain database to display threatening terrain. And although it is a fantastic tool, a wise captain cautioned me many years ago to always have a plan in case technology fails. Radar is a system that operates independent of derived aircraft position and independent of any internal database. It is an outstanding tool for maintaining SA regarding terrain.

I�m lucky because I can display TAWS on one multifunction display (MFD) and radar on the other�two completely independent systems that should mutually agree regarding the terrain around the aircraft. For anyone who does not have TAWS, the radar may be the only system you have to maintain terrain SA at night or in IMC.

Two simple techniques can help you do this�provided the radar is functioning properly, the antenna is correctly aligned, and the pilot has a basic understanding of how radar works. Remember, the radar should be used for whatever poses the biggest threat; sometimes that will be weather, while other times it may be terrain. It can also be both simultaneously.

For those who have attended my program at any of the previous Twin Commander Universities, the following two techniques will be review. One of the three tilt positions is the Threat Identification Position (TIP). This is the tilt position that results in the bottom of the beam sweeping parallel to the plane of the earth. The purpose of this tilt setting is to identify threats that exist at or above current aircraft altitude.

TIP is accomplished by raising the tilt one-half the beam width above 0 degrees. The beam width for a 12-inch antenna, like those found on Twin Commanders, is roughly 8 degrees. So TIP would be about +4 degrees. With the tilt set to +4, any object you observe on radar that is on your intended flight path means impact is imminent�weather, terrain, or otherwise.

The second technique uses the primary tilt position�the Normal Antenna Position (NAP). This is the tilt position that results in the bottom of the beam being down approximately 4 degrees. For a 12-inch antenna, the tilt would be set to 0 degrees. NAP can provide SA for several threats, but let�s focus on terrain clearance. First, assume 2000 feet is the desired terrain clearance (personal preference can dictate it should be more). Using NAP, don�t let any ground returns inside 5 miles. How did I derive that? I know that 1 degree at 5 miles is approximately 500 feet, therefore 4 degrees (bottom of the beam) is approximately 2000 feet below the aircraft at 5 miles range.

Again, look at the photo; the magenta line (flight path) cuts through a gap in the mountains and there is no terrain inside of 5 miles anywhere on my depicted flight path. It remained this way until we were abeam the field, when we descended below 2000 feet AGL. Predictably, at 1000 AGL (roughly 3-mile final), ground returns had crept back to about 2.5 miles on the display.

You may prefer using TIP instead of NAP, and that is fine; either technique will keep you from becoming a CFIT statistic. Why did I use NAP that night instead of TIP? Because weather was not a factor, and there were other tasks that took priority over adjusting the tilt. It was still 100-percent effective in providing SA regarding the terrain. Either technique works on departure as well, although TIP may be the preferred technique for most.

Two final caveats must be mentioned. First, most radar systems will detect some energy outside the beam width stated by the manufacturer. For a 12-inch antenna, the stated beam width typically is about 8 degrees, however, because terrain tends to be more reflective than weather, it is common for the actual beam width to be slightly wider than stated.

Most radar system beams are 2-to-4 degrees wider than stated, but depending on the year it was manufactured, the RDR-2000 and the RDR-2100 may even be slightly wider than that. So with TIP set, you may see terrain during descent slightly before you�re actually below it. Or, with NAP, you may see ground returns at 5 miles but have slightly more than 2000 feet clearance. This brings me to my final caveat.

Radar proficiency is a must. Practice on clear weather days until proficiency is achieved. Practicing these techniques on a clear day provides the opportunity to observe the characteristics of your specific radar regarding terrain. Find the technique you like, and practice until you are comfortable with it.

And, always use the radar at night or in IMC. If hazardous weather is present, then you should strike a balance between using radar to detect both weather and terrain. Busy? Yes, but this further validates how critically important it is to be proficient with the radar and to be able to use it to its full potential in a manner that is second nature.

Practice as if your life depends on it, because there may come a day when it actually does.

Discuss this article in the forums...